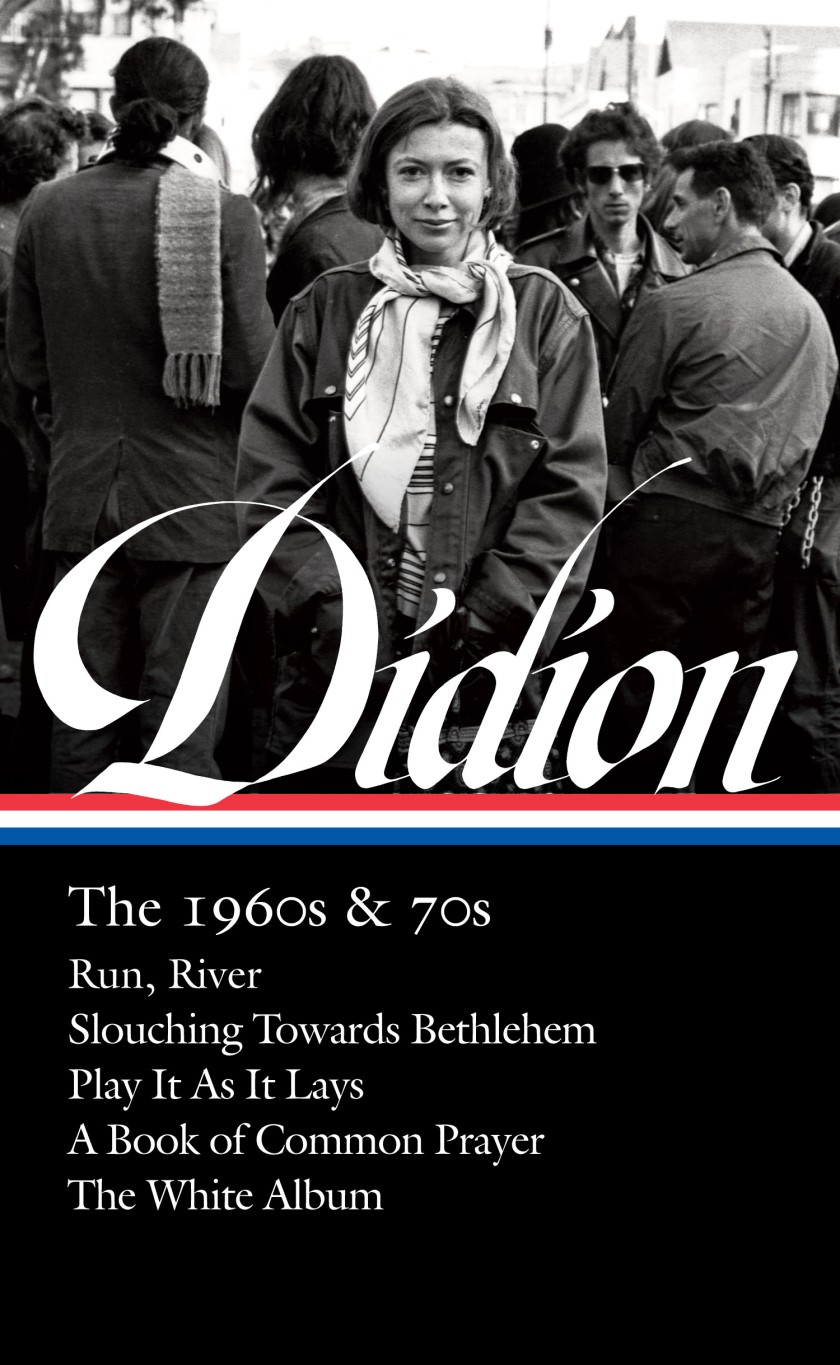

The sequence is as predictable as the season itself: The calendar reads “fall” but the thermometer registers 90-plus. The Santa Ana winds kick up. Wildfires zipper across the landscape. Once again Joan Didion whispers in the Southland’s collective ear.

“I have neither heard nor read that a Santa Ana is due, but I know it, and almost everyone I have seen today knows it too,” she writes in “Slouching Towards Bethlehem.” “We know it because we feel it. The baby frets. The maid sulks. … To live with the Santa Ana is to accept, consciously or unconsciously, a deeply mechanistic view of human behavior.”

Novelists, essayists and poets, photographers and painters have all evoked the region in its inscrutability and calamity, but Didion’s measured cadence is embedded in our consciousness. Tropes become burrs. We come to her for dusty palms, pepper trees, eucalyptus, the “soft westerlies off the Pacific,” but also the concrete overpasses, cyclone fencing and deadly oleander.

It’s home. The truth of it. Hot pavement under our feet. She has written hauntingly about disasters — both acts of God and man-made mayhem, from runaway wildfires to Charles Manson — that have rewritten the narrative of this place. Pared down: For many she articulates California’s particular seasons, a West that is as recognizable as it is changeable.

to read the rest of the review click here

By Lynell George/via LMU Magazine

By Lynell George/via LMU Magazine